Quotes:

“People in contemplation are assisting in bringing about a major planetary shift in consciousness…..They’re assisting in the Dream of the Earth.”

“On the river, there is this harmony and peace. You’re in union with the flow and the trees and the birds. I think it is so important we realize that we are part of the Earth and the Earth is part of us.”

“The natives, they have this wonderful sense that the universe, the Earth, is filled with spirits. The Great Spirit is there, so they don’t spoil it.”

“…..people don’t want to be disturbed……They don’t want their balance upset. But if we don’t face the Dream of the Earth, then where are we going?”

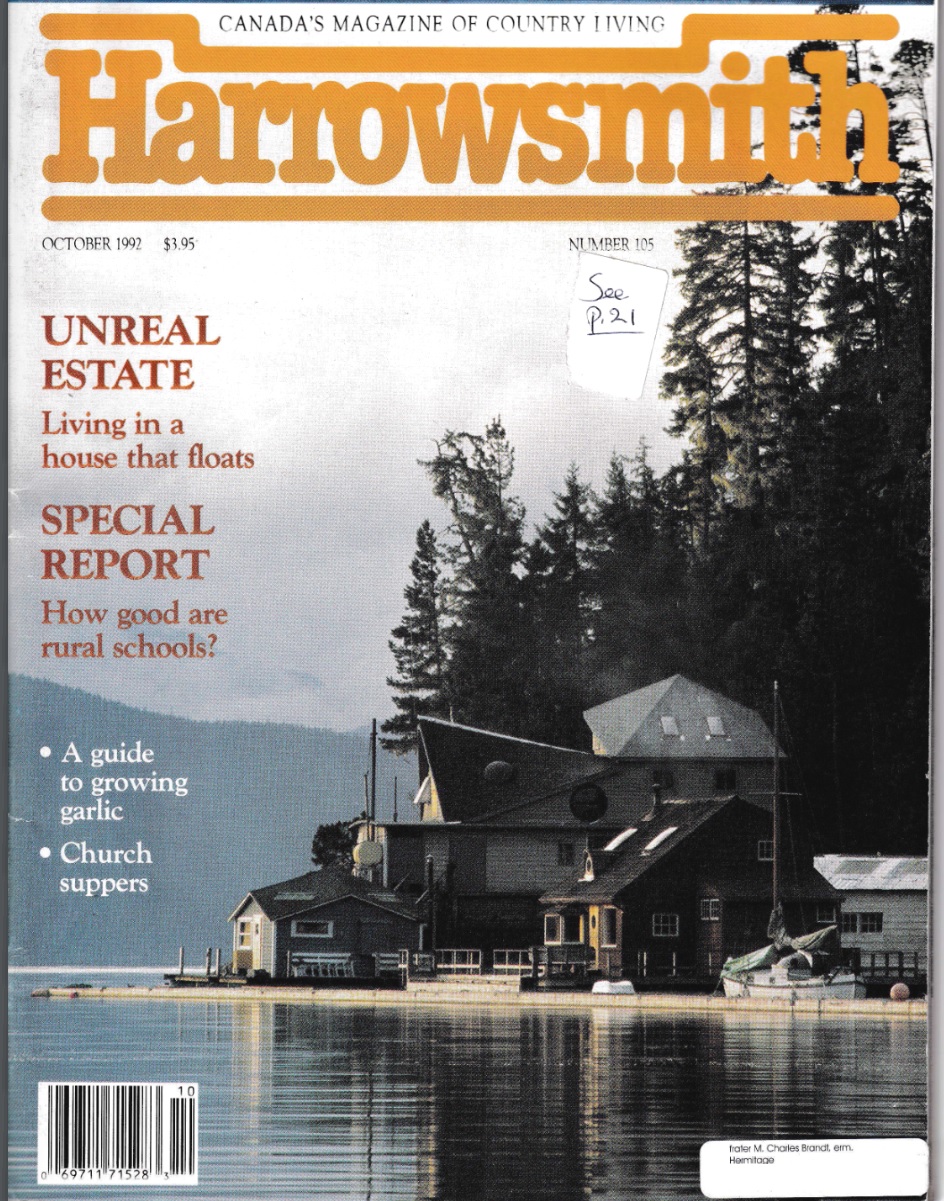

The Hermit Priest by Mark R. Norrie – Harrowsmith Oct 1992

There is a place near the top of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, where a man sits on a rough, sun-bleached cedar bench, staring at the Oyster River, which flows a few yards below. Often he walks the river bank, on worn paths through massive fir and cedar trees. He walks not to reach a destination but merely for the sake, he says, “of placing one step in front of the other.”

Sometimes, too, he stands in the middle of the river, the chilling mountain runoff encircling him, lapping at his green-rubber-clad legs as he rhythmically casts his fishing rod. And while he does all this, Father Charles Brandt is thinking. He is contemplating and meditating: about God, Earth and humankind and how far apart the three have grown.

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that when I sit beside the hermit priest on his wooden bench above the river, I am struck with the image of a sentinel guarding the Earth and all its inhabitants. He stares silently at the natural world around him, ignoring-even enjoying, I think-the mild drizzle that is falling this morning.

Indeed, ever since Father Brandt came to Vancouver Island 25 years ago and was ordained a hermit priest, the first in the Catholic Church in nearly 200 years, he has watched over the natural world, working hard both to protect it and to awaken a new understanding toward it.

“People in contemplation are assisting in bringing about a major planetary shift in consciousness,” he says, his soft, hushed voice barely audible above the roar of the Oyster River. “They’re assisting in the Dream of the Earth.”

For Brandt, the “Dream of the Earth” is an enlightened realization by humanity that “the universe is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects to be exploited.” A tall man with slightly stooped shoulders, balding head and bushy grey beard, Brandt would not look out of place in a university chemistry department. But neither does he look out of place here in the forest. Just as his black corduroy pants and dark blue sweatshirt blend perfectly with the shadows of the massive cedar trees, Brandt himself suits his environment, giving me the impression that his beard and the bench on which he sits turned grey together.

Brandt was born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1923. His childhood hero was Henry David Thoreau, who said he went to the woods “to see what life was all about.” The young Brandt vowed to do the same, although it would take more than 30 years before he did so. In the intervening time, Brandt served as a navigator in the United States Air Force and obtained Bachelor of Science (majoring in ornithology) and Bachelor of Divinity degrees.

Ordained an Anglican priest in 1951, Brandt converted to Catholicism five years later and, in harmony with the second Vatican Council, explored the origins of monastic life in the church and worked to re-establish its lost traditions. Brandt discovered that the members of his religious order, the Cistercians, who follow the rule of St. Benedict, were originally hermits. In 1965, drawn to a life of “deeper silence and solitude,” Brandt left his Trappist monastery in Iowa to join a group of theologians and scholars who had established a colony of hermits in an abandoned logging camp beside the Tsolum River, north of Courtenay on Vancouver Island.

Complying with the colony’s principle that each hermit “must earn his own bread, Brandt pursued bookbinding, which he had studied in Iowa. Eventually, when the hermitage developed into such a sizable community that it ran counter to its original intent, Brandt bought 30 secluded acres on the banks of the Oyster River, near Black Creek, and trucked his plain wooden house and workshop farther up the island.

While believing strongly in prayer and meditation, Brandt soon learned that it was necessary to work on more earthly levels as well. When a marina was proposed for the mouth of the Oyster River, Brandt was among the local people who fought to stop it. The attempt failed, leaving Brandt “broken hearted” but with a new appreciation for the value of rallying media and public attention.

After leaving for the United States and Europe in 1973 to expand his knowledge of bookbinding and to learn paper and art conservation, Brandt quickly became skilled in those fields and was asked to work in museums in Moncton, Ottawa and Winnipeg, where he was given the task of restoring decaying books and paintings.

Returning to his hermitage in 1984, Brandt was shocked to find that the Tsolum River was considered “dead” because of poisoning from the abandoned Mount Washington copper mine. The mixing of water and oxygen with exposed waste rock had created a copper leachate that filtered into the river, annihilating fish and plant life. “What was once a wonderful salmon river was degraded,” says Brandt.

Distressed, he attended a meeting of the Comox Valley chapter of the Steelhead Society of B.C. and emerged chairman of the Tsolum River Enhancement Committee. Thus began the ongoing six-year battle to pressure the provincial government into cleaning up the old mine site.

With Brandt spearheading the project and spending countless hours writing letters and contacting politicians, the committee eventually succeeded in getting the government to commit $1 million toward the project, but not before Brandt had roused media interest and announced that the committee itself would campaign to raise the funds for the cleanup.

In 1989, the Steelhead Society of B.C. honoured Brandt’s work on behalf of the Tsolum River and other environmental causes by awarding him their prestigious Cal Woods Award. In 1991, Brandt’s continued environmental efforts were again recognized when he was presented with the Roderick Haig-Brown Conservation Award.

Though somewhat shy of the attention the awards have brought him, Brandt clearly is honoured by the recognition. “I knew both Woods and Haig-Brown personally,” ‘he says. “They were great naturalists, and I liked and admired them both.”

Brandt has plainly decided to take advantage of the resulting media coverage to disseminate his views on what is happening to the Earth.

“On the river, there is this harmony and peace. You’re in union with the flow and the trees and the birds. I think it is so important we realize that we are part of the Earth and the Earth is part of us. The natives, they have this wonderful sense that the universe, the Earth, is filled with spirits. The Great Spirit is there, so they don’t spoil it.” The aboriginal approach to the world is known as perennial philosophy, explains Brandt, an approach abandoned by the Western world in the 17th century, when influential thinkers like Rene Descartes, Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton came to look upon the universe as a mechanical system without spirit or consciousness. This, he argues, eventually led to the Industrial Revolution, the development of the atomic bomb and the current tragic state of the environment.

“Now quantum physicists are telling us,” says Brandt, “that everything is interrelated. Now they are saying the universe is a complicated web of interdependent relationships. It’s like the Oyster River watershed: everything is interrelated. It has probably been here for 10,000 years. The valley is 25 miles long and is an entire bioregion, but in the past hundred years, humans have completely upset that balance.”

Brandt says that at one time, the Oyster River had hundreds of pools and gravel bars, but now the pools are filled in and the gravel has been washed to the mouth of the river. The cause, he is sure, is clear-cut logging. Clear-cuts have created uneven flows – extremely high in winter and extremely low in summer. Algae growing in the river may threaten the fish that remain. “But people don’t want to be disturbed,” he sighs, locking his gaze on a stump being carried quickly out to sea. “They don’t want their balance upset. But if we don’t face the Dream of the Earth, then where are we going?” For the pessimistic among us, it is a daunting question. Still, one may find solace in the knowledge that wherever the Earth is heading, Father Brandt will be meditating at his post above the Oyster River, guiding us as best he can.