by Father Charles Brandt

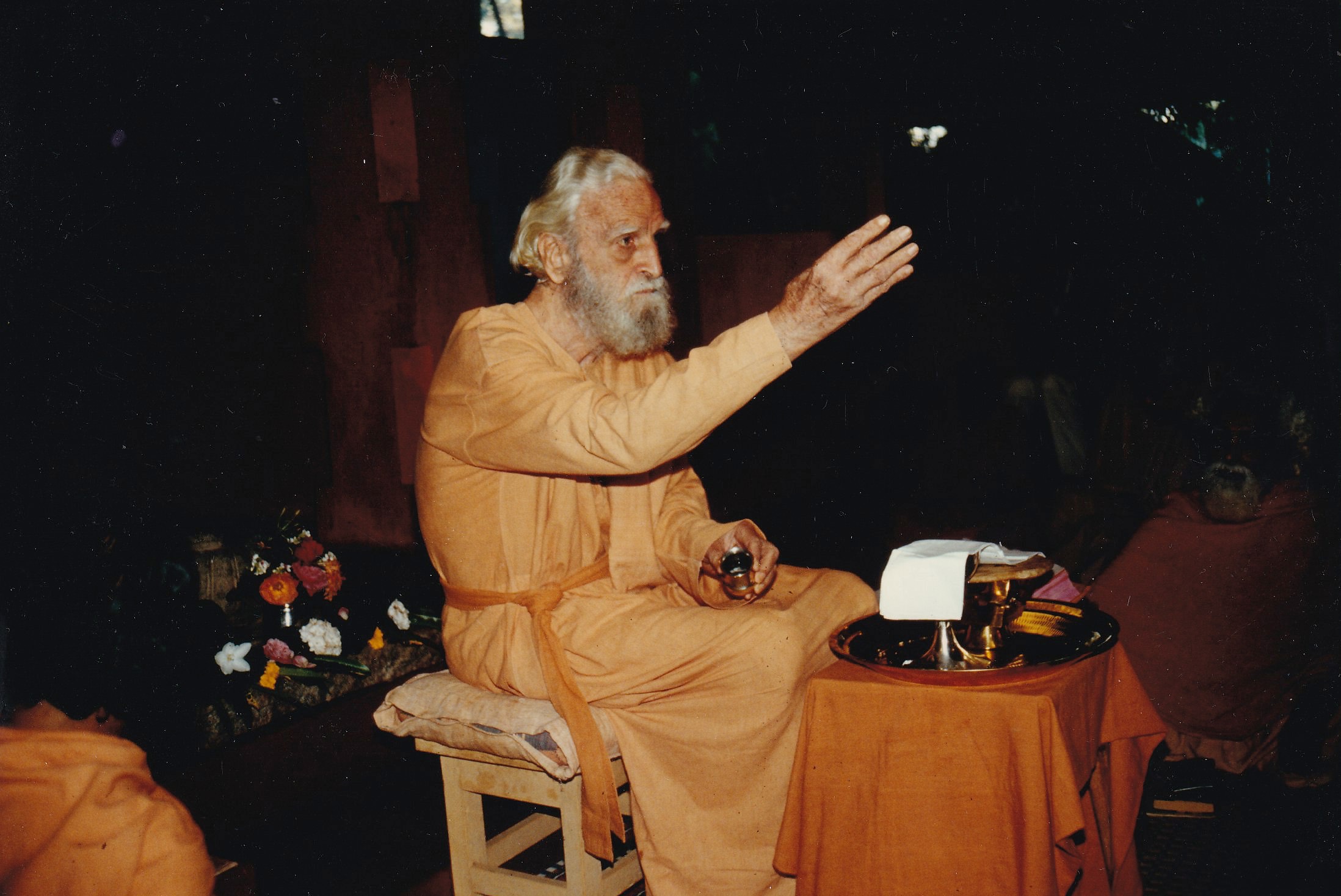

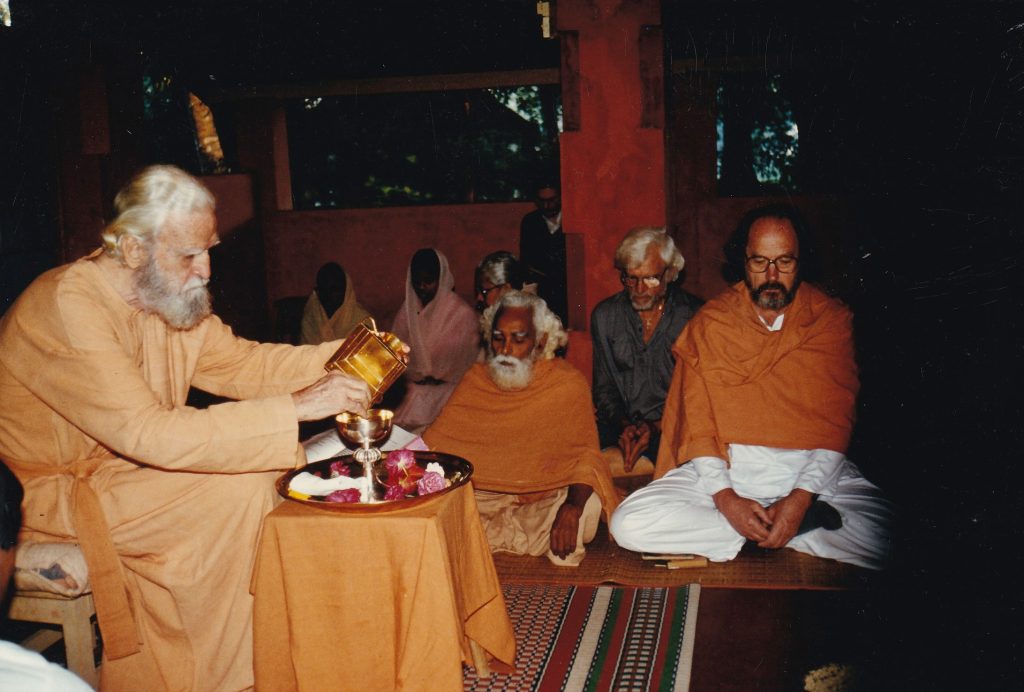

In 1989, Father Charles Brandt travelled to the Shantivanam ashram in India to spend two months with Father Bede Griffiths who had a strong influence on Charles becoming open to the meditation practices of the East. Before his trip to India Charles mentions his plan for this upcoming journey and Bede’s book of about the Marriage of East and West in his interview with Judy Hagen on his contemplative life. Charles in many respects was following a path of Thomas Merton, Thomas Keating, Hugo Lasalle, John Main, Lawrence Freeman, Abhisiktananda, and Thich Nhat Hanh in linking the wisdom traditions of East and West. The following is a transcript of a video between Fr Bede Griffiths and Fr Charles Brandt.

INTERVIEW WITH FR. BEDE GRIFFITHS by FR. CHARLES BRANDT transcript

Dec. 3, l989, in Bede’s Hermitage, Shantivanam, India

C: OK, first of all I’d like to discuss with you a little bit about Christian Meditation.

B: Yes.

C: You know, I give retreats and I spent a month at the Priory in Montreal just so I could really understand it…

B: Yes..

C: …and I really admire John Main’s teaching…

B: yeah…

C: …and I know the other day you mentioned that you had given out something like ten books on John Main, so you must think highly of him.

B: Very highly. We almost make it a model, you know, here.

C: Do you ..I know … you thought he was the really outstanding spiritual director of his time..

B: Yes. I feel he’s opened this prayer to interiority in a way in which hardly anybody else does.

C: I see..

B: Yes.

C: …and you know he’s…you met him down at Mt. Saviour…

B: I met him only just for a few hours, you know…

C: uh hum… what was your impression of him?

B: ah..it was simply good; I didn’t go really deeply into it, you know.

C: I see. He spoke at the Cathedral in Victoria – that’s my diocese. I didn’t hear him but I know that it was kind of mixed, some people went absolutely fond of him and he sort of alienated other people. He would … was very military in a way, you know, in his approach and, ah, very insistent that there is one way…

B: yes..yes..

C: …to practice…

B: yeah…interesting…yes. I don’t take him too strictly like that but what I feel is that he spoke from the heart always, you know, from deep experience and that gives such power to his writing and what he said. I find power in it which I don’t find in most writing.

C: ahm…it came up from his own experience…

B: His own experience. He lived it totally.

C: Absolutely. I think that’s true. You know, we’ve talked bout this before… this business of the continuous and discontinuous mantra…

B: Yes.

C: … and he’s very strict about that…

B: He’s very insistent, isn’t he.

C: Yes he is, very… almost rigid about that.

B: Yes, well, I think, you know, he was introducing a method of meditation and he felt it was important to…to give people a definite method, you see. People don’t know anything…

C: hmm..

B: You see this was a real lack. People were looking for this deeper prayer, this interior prayer and they had no method, you know. The Ignatian method was the only one and that’s discursive. It’s not very contemplative, you see.

C: Right…right…

B: So he found this need and he… and he found the answer and he felt the need to insist that people learn the method, but maybe he was a little too strict about it.

C: hmm…

B: And certainly I don’t follow that… this with the mantra. I follow centring prayer rather more with that.

C: Do you? Father Keating…

B: Yes…

C: … and Pennington approach.

B: Yes. I don’t find much difference between them. They both centre on the mantra but he focuses…keeps the mantra right to the end and they say when you reach the interior awareness then you can leave the mantra. You see, in any case I am very much against a rigidity of a technique, you see. A technique is there… you need it to get you going .

C: He would never say it was a technique; he would say it was a discipline.

B: Yeah…yes (chuckles)

C: A kind of technique…You know, I wrote to Fr. Keating about this once and…

B: aha…

C: and, ah, he said, well, you can get there both ways…

B: yes…

C: …but he thought the intermittent mantra might get you there more quickly and it might destroy get rid of much of what’s in the, ah, subconscious much more quickly. I don’t know how…

B: Yes..

C: …how…

B: Yes. I rather feel the same. I find Thomas Keating…to some extent… I think I put him above Fr. John Main, in some ways.

C: I see.

B: Particularly recently he’s… so far….that book Open Mind Open Heart…

C: That’s a beautiful book – especially fine on the history of contemplation in the Church and what happened… the Reformation…

B: Yes..

C: …the Hundred Years War and how we lost it…

B: …how we lost it…

C: …and how we’re regaining it.

B: yeah..

C: yeah… I think he’s especially good on that. Another thing I wanted to ask you about was the eremitic

life…

B: yes..

C: As you know, I’ve lived that now for something over 20 years… and it seems to me that in one of your writings – perhaps it was in Monastic Studies – you were talking about the East and talking about the rishis going into the forests as hermits…

B: yes…

C: …it’s almost as if today in India we need a different form, form of a communal life. I wonder if you feel that there is no need for hermits today.

B: Oh no. No definitely I feel the need. We’ve joined Camaldolese now, you see and they have this twofold

community life and the eremitical is fundamental …

C: I see…

B: One of the reasons why we joined them, actually.

C: …mm

B: They’ve been a little too insistent that community life is a preparation for the eremitical life, but now they’ve balanced it better and they see them as complementary where you can go from the community to the eremitical but you may also want to pass back from the eremitical to the community at times so they’re not at all rigid over it. But I think we all feel very deeply a deep need for solitary life… for

solitude and silence. I think its one of the greatest needs. I’ve changed a bit….

C: ..have you…

B: I was very much for community life.

C: I see.

B: It was only after I came to India that I began to see the value of the solitary and now I feel it more than ever, perhaps, you know.

C: Do you feel, say, your members of your community here, the Camaldolese have that opportunity for…

B: Yeah.. the Camaldolese definitely and here we encourage it and for a short time many of the brothers like to take a week or so of silence and solitude and now at the adjoining ashram where you are, Marie Louise’, people who want a long time of silence, maybe six months or a year, they normally go there.

C: I see. It’s really… I find it excellent.

B: It’s excellent, you see…

C: Yes it is…

B: …and we encourage that very much.

C. I see. That’s good to hear. OK, now, next thing… we touched on this when Roland Ropers

was here and he gave the talk on Zen…

B: ..yeah..

C: By the way, I though he was a little bit incorrect when he was talking about contemplation as being image prayer, you know…

B: Yes, I think it’s their use in Germany or something, it’s not normal at all.

C: I see… like when we mean meditation in Christian Meditation we’re talking really about contemplation.

B: Contemplation is without any images.

C: Right. OK. Now the ego. I’m, you know…in psychology, psychologists use the ego, it seems to me, in a very different sense than we might in spirituality. The Thenia and the Buddhists, they talk about reaching an egoless state, that there is no longer an ego…

B: The Hindus do also…

C: And John Main said that meditation is an onslaught on the ego.

B: …yeah..

C: OK, now the point is, what is the ego, and is there something good about it. Now Christ had an ego and…is there something good, or is it totally bad… or …B: No. I think from a Christian point of view it’s definitely something good, and we have to balance that a great deal. The Buddhist and the Hindu can be very misleading in my mind, you know and we would emphasize the ego is part of the personality. Actually in the Hindu tradition, you know, you have the manas, the rational mind, in a sense, the buddhi, the intellect, pure intelligence, and the ahamkara, the “I”

maker and that is the centre of the personality, actually, you see, the ego. But in the Christian view, we would say to build up the ego is necessary and psychologists say so often people don’t build up a sufficient ego centre, you see. But then, we say, when you’ve achieved your ego you need to go beyond it, you see, that’s the problem. You have to find..to build up the self, the ego, but then the danger is you become self-centred and when you say “get rid of the ego” we mean the self-centred personality, the person centred on itself, you see…

C: …seeking esteem, and power and so forth, that kind of…

B: Yes. And to me that is the essence of sin, you see, this fall from an open self, open to God and to others, to a self-centred separated, a separated self. The self should never be separated; you should always be in communion with your parents, you family, your people, with others, with God, you see. The self is a…a.. what do you call it…a being, a personal relationship. It’s essentially a personal relationship and when it closes on itself, it becomes destructive, you see. That is the great evil. I would say original sin is the fall from the self which is open to God and to others, the spirit, the pneuma, into the ego, the

psyche, the self which is centred on its own activities and so on…yes…

C: OK. What about Christ on the cross when he cries out…Eli Eli, lema sabachthanai…

B: yes..

C: Now it seems as if he lost that sense of relationship or of sonship to the Father. That it disappeared, he lost…he seems to have lost his very self in a sense …

B: Yes..

C: Could you interpret that as he was moving to a greater self… I don’t know…

B: That’s a very interesting point. I rather think you can, you know. I think the Heavenly Father was the way he imaged as a human being, he imagined God, you see. His Father, himself as Son and I think he broke through every image, you see. It’s the dark night of the soul of the spirit… the cross, really. And he got beyond any, ah, differentiation, like that, you see. Passed beyond…

C I see.

B: That’s one interpretation. I find it a very interesting one.

C: Yes.

B: …very interesting…

C: I do too.

B: It’s not just negative. There’s something very positive…

C: hmm…hmm…hmm. Father Bede… about Perennial Philosophy… you say in your writing there was a period… what do you call it… the axial period….

B: yeah, yeah…

C: Sixth century, approximately, before Christ when all the great religions…they had this..ah.. perennial philosophy. I’m not sure what it is. But I think of it as everything being made up physical, spiritual and psychical… and they had a deep wisdom that related themselves to the universe and gave them some sort of a basis for living joyfully in community with nature….

B: …and a wholeness…

C: …and a wholeness… and somehow we lost that after the Renaissance….

B: …particularly after the Renaissance…yes.

C: Now, how would you say we lost it. I understand with Newton’s coming and the mechanistic world…

B: Usually Descartes is the dividing point, you see. That separation of mind and matter… are separated, definitely, but God remained. And the next stage was having separated mind and matter, you were separated from God and you didn’t need God any more and the thing has gone down like that.

C: Right. So to regain that in the West, what would be the steps?

B: That’s why we… I mean that… look at what Rupert Sheldrake is doing… you’re not there…

C: I ‘m reading about morphological…

B: Morphogenetic fields…

C: It’s almost like Artistotle’s forms, it seems to me..

B: …form as matter, yes. We’re reading his new book in the refectory. And he is fascinating. He completely rejects, and demolishes really, this, ah…where there’s matter in motion of Descartes and Newton, you see, which is the present scientific orthodoxy and insists that matter and the earth and the universe is a living organism; it’s an organic whole, you see.

C: You’re talking about Gaia, now.

B: It’s a Gaia, Gaia, you see. And so in science we’re recovering … getting over this terrible split between mind and matter, you see…between human beings and the universe , and we’re recovering that wholeness of mind and matter. And then he shows that once you get this unity of mind and matter you discover you are integrated in a greater whole. You open yourself to the transcendent which is within both

mind and matter, you see. To me body , soul, and spirit, you see is the key. That’s the Perennial Philosophy.

C: Right.

B: One’s never lost. There are three levels, you see, in any tradition you find…

C: …in everything – in the tree there’s body, soul, and spirit.

B: Body, soul and spirit. You see, there’s always the psychological aspect, psychic aspect of matter and life and the spirit permeates and pervades the whole…

C: hmm…hmm…

B: … and this is the holistic vision of the universal which I think is spreading now in science and philosophy and religion, you see. We’re recovering a wholeness which we lost mainly at the Renaissance. And its fascinating, really, the way its spreading. This book of Rupert’s I think is a very important step but it’s coming out everywhere. People… from the point of view of physics or biology or psychology or religion… people are discovering this wholeness…

C: …this complicated web of interrelations…

B: …complicated web of inter-related..

C: …of interconnections…

B: That’s right.

C: Speaking of consciousness. That’s the next thing that… you know, Chardin, he talks about even stones having a simplistic sort of intelligence and this evolution of consciousness that reaches perhaps its peak in human beings… You know we look at matter today and even the smallest particles…. we don’t even say they are, ah, physical entities… sort of motion, dynamic energy…

B: Yes.

C: … but what is consciousness? What is it?

B: I think, in those terms, you see, we say the universe is this web… is a field of energies … is a field of

energies, that there is intelligence present in that field of energy from the beginning, structuring atoms, molecules, cells…

C: You’re talking about God, now…

B: …no, simply an intelligence is present. I mean, it’s in nature, you see…

C: It’s in nature…

B: It’s in nature. The intelligence is present in the atom, molecule, you see and so…

C: …so what is this thing…

B: Now that’s the point I would say in human beings…that intelligence working unconsciously in nature comes into consciousness. We are the point where nature becomes conscious. The intelligence working in nature becomes conscious in us, you see.

C: OK. Is this a psychological thing?

B: Yes.

C: Is the spirit…

B: It’s psychological.

C: It’s psychological…

B: It’s psychological..yeah… and then once you discover that you are in harmony with an intelligence working in matter, in life and the world around you, you open yourself then to the discovery that there is a transcendent consciousness, a transcendent power which is working through matter and

through you and to which you are connected consciously, you can then consciously relate yourself to the source of all, you see.

C: … so then our consciousness, not this higher consciousness, but our ordinary consciousness is very much tied up with matter…

B: It’s tied up with matter, you see…

C: …very much so…

B: …that is body/soul, psychosomatic element, but then you discover, beyond your normal limited consciousness, you open yourself to the transcendent consciousness then you find God. That is Karl Rahner, you know. Do you read him?

C: Some, yes.

B: I found him fascinating because his whole theology, really, his philosophy, really, rests on this view that the human being is constituted by the capacity for self-transcendence.

C: Yes, I remember that, yes.

B: Holy mystery… we open on something beyond, you see. That’s the key to human nature, and then we explore that holy mystery and it reveals itself to us and so on. But our consciousness is consciousness coming out of matter, the body, the senses, the feelings and so on, but opening itself onto the transcendent.

C: So it’s almost…a physical/psychical thing.

B: It’s always physical/psychological and spiritual, you see, always in the three aspects of it.

C: Right.

B: …and that’s where materialists and people have a point, you see. It’s not simply spiritual ever, it’s always the matter is involved in it, just as in the final state the resurrection of the body, you see, is the whole, ah, field of energies of nature becomes fully conscious and is taken up fully into the Divine consciousness.

C: hmm…beautiful… it is right…You know, ah, in the new physics, ah, they say that somehow the human consciousness is essentially involved in the object which it observes… now I’ve talked to people back home on Vancouver Island, a scientist, a fisheries biologist and he seems to interpret that…”well sure, because our instruments are so imperfect, therefore we’re involved…” But aren’t we talking about

something much deeper than that? That our consciousness somehow enters into the very working of the experiment and affects it in some way?

B: Yes. I think that came out in quantum physics, you know. If you change the instruments, you change the results. You know, sometimes you get particles, sometimes you get waves. So we affect what we’re observing. But then we have to take it a stage further and say, you see, that the very way that we observe anything depends on our minds, you see. We… the fact that we, ah,…observe anything, this chair or

something..ah…we’re always connected with it, you see. The chair is…there’s an energy here and that energy affects my senses, my senses affect my brain and then thought emerges from that and so human experience is an interaction between matter and mind. It’s never separated, you see. It’s an illusion that

you’re learning something outside yourself. Some of the best scientists have said that quite clearly now, you see. It’s really come through. But the ordinary scientist still doesn’t believe it, you know.

C: People like maybe, Chew…and…

B: Yes…I’ll tell you the man…I just put it in the library…this book, do you know… The History of Time… A

Short History of Time…

C: No.

B: It’s a man called Stephen…Stephen…names suddenly go out of my mind….Hawking…

C: Stephen Hawking…

B: He’s a scientist in Cambridge and he’s a cripple…

C: Oh yes. I know who… I’ve seen him. Supposed to have the most brilliant mind…

B: Brilliant mind!

C: ..yes, yes…

B: …and he’s written this book, but he’s really a Cartesian scientist. He really thinks that his mathematical

exploration of the universe…he’s discovering the real nature of everything and if he can get it really worked out, he will have the mind of God, he thinks. Extraordinary!

C: Fantastic, yeah… just to tell you something slightly…slightly… I’ve been reading about Pere Monchanin and one of the books I read claimed that even he was a Cartesian in his spirit, huh? Yes. He was very, you know, ah… he was all for production; he wanted India to get more into technology…

B: Which book was that?

C: OK..the one… It wasn’t Webber. It wasn’t Swami Parmi Arubi Anandan,

B: Ah!

C: I think that it was in one of the letters. You have a letter in there, yes…

B: That’s new to me because Fr. Le Saux, Abhishiktananda, always said he was a Greek and he says the same thing, he’d got this Greek rational mind…

C: Right, right, right, yeah.

B: ….big limitation.

C: You know, before, we talked a little bit about, about Wayne Teasdale. I knew that he’s probably done more than anybody else to sort of… consolidate your studies, “Bedian Studies”, he said. How do you feel about Toward a Christian Vedanta which I’ve read several times, by the way.

B: Yes.

C: Do you feel that that really is…

B: I think it’s extremely well done, you know, but I think at the end we really part. You know he’s too Cartesian really. You remember he wants to arrange everything and some people are nearer to the fullness and some are a little further away. He’s got it all mapped out in a way which I wouldn’t accept.

C: I see.

B: But I’ve changed myself a lot, you know.

C: That’s what…you know. I don’t know if you’ve ever ready any of Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of the New England transcendentalists that lived in Concord, Massachusetts in the 19th century along with Henry David Thoreau, people like that. He said, “I contradict myself, or I change my mind: very well, I contradict myself and change my mind.” That’s growth you know…

B: Yes.

C: …that’s what he was saying…

B: That’s what I find the same. I’m amazed what happens now even now. Yes, it’s going on all the time, but I’m supported by Newman also. Newman said, “To live is to change and to live long is to change many times”.

C: That’s right.

B: It’s true. Change is growth. That’s exactly the point. Growth is change, you see. And to grow continuously is to change, subtly of course, and so on. But most interesting I find.

C: In Toward a Christian Vedanta I was especially interested in his treatment of your Christology and Christ. You point out…Christ… he never said that he was the Father. He calls himself the son of man and so forth. I think somewhere in your new Book A New Vision of Reality … even the statement, “Before Abraham…”

B: …was I Am.

C: …that could be interpreted in an archetypal sense. In Christian Vedanta when he’s treating of your Christology he mentions Christ, you know, the three levels of being, body, soul and spirit. OK in body – and this is interpreting your thoughts – in his body and soul he was limited to some extent, so he was in a sense less than God.

B: Sure, yeah.. What we traditionally call the human nature of Christ, you see.

C: … he didn’t know when the end of the world was coming and things like that. But then you say in his spirit, because he was completely filled with spirit, that we could say that in that sense he is God.

B: Yes. That’ my idea. I would say every human being at the point of the spirit is open to the Holy Mystery of the transcendent but we are all limited and I think in him the spirit..uh..in him dwelt the fullness of the Godhead bodily. The spirit was totally open to ascend to the Father, you see.

C: …but nevertheless in his human nature…

B: …but it’s the body/soul…

C: …he had a…had a human spirit…

B: Yeah…well, you see the point of the spirit is precisely that. It’s the point of human transcendence, it’s both.

C: The Holy Spirit touches our spirit.

B: The Holy Spirit touches our spirit and transforms it and so that point of the spirit in Jesus, which is a human point of the spirit, was totally open to the Godhead, you see.

C: From the very beginning…

B: From the beginning, yeah..

C: …from his very birth, infant life…

B Yeah, because otherwise I wouldn’t say of anybody else but him had got the fullness of the Godhead.

C: OK now…here’s the… I’ve been studying your book…

B: … the new one. Have you still got it?

C: Yes I do. I”m finishing it up now. If got it from Eusebius.

B: You got it from Eusebius. If I could have it back sometime, because people are asking for it.

C: Alright. I’ll try to get it back to you.

B: No hurry.

C: OK. By the way, this…. I came across this title, “A New Vision of Reality”, in one of Capra’s…

B: Capra, yes… I mentioned it in the book.

C: Oh, did you. That’s where it came from.

B: Yes.

C: OK. Now, I’m just going to read this because this is something to me is very important. You say, “At the

ascension matter is transformed. The matter of the universe is taken up into the Godhead…”

B: yeah..yeah.

C: Are you talking about all matter?

B: Yes.

C: …this bed, this…

B: …the field of energies, all this is part of the field of energies and it’s structured in this present time/space order in our consciousness, but as our consciousness is transformed so this field of energies with its consciousness within it, is totally …ah…pervaded, penetrated by the Spirit, you see. Body/soul/spirit again, and the body and the soul as they are penetrated by the Spirit are

transformed into a spiritual body and a spiritual soul, you see. It’s a total transformation. It’s the new heaven and the new earth, you see, of the Biblical duality.

C: OK. Now you go on to say in Jesus consciousness finally took possession of matter and this means that the matter was spiritualized. In him the matter of the universe was, in other words, made totally conscious. He became one with God and the Godhead…

B: …that’s the idea…

C: …now, are you saying that all matter out here that I’m seeing – the trees and the plants and so forth – is

conscious with the consciousness of God?

B: Well, you see, we are seeing it with our consciousness where it appears extended in space and time, you see, out there and so on, but when you are transformed by the Spirit, your mind and body transformed, then you’ll see the whole of the universe not extended in space and time with its limitations but in the fullness of being in the Godhead. That is the heaven and you’ll be there.

C: So that’s already taken place with Christ …

B: ..yes, in our present mode of consciousness we still live in the dualistic world, you see. But in his consciousness which we also hope to rejoin, there will be no division at all, you see. Total oneness. Like… I quote Boethius, you know, that eternity is the total and simultaneous possession of unending life. Total and simultaneous. What we now see separated out and changing we there see totally one and unchanging… all gathered into fullness.

C: Really awesome, isn’t it?

B: It’s awesome. You see, the value of it is it shows that this world is real, the trees, the earth, you and I are all real, but we don’t see the full reality, we only see a partial aspect of it, you see. Because we see it in space and time, but when we go beyond sp…when our consciusness goes beyond our present limited state, then we shall see it as it is. And we shall see Him as He is and we shall see ourselves as we are and the universe, you see, as total oneness. It’s non-duality. It is the ultimate reality. We’re still living in a dualistic universe with a dualistic mind. But when we go beyond, the whole reality is there in a non-dual way.

C: Yes, yes. Beautiful.

B: It’s really wonderful when you think of it, because so often you either have a level which is spiritual and beyond and all the rest goes, or else you’re stuck with your material universe, you see. But this really…

C: Ah..you know, I think of Christian prayer – and I think I got this mainly from John Main, probably, in The Present Christ – that the human consciousness of Christ exists now; it’s infinitely expanded but it’s now, it’s here, it hasn’t disappeared and when we pray, if it’s really prayer, we enter into that same consciousness, in this stream of love to the Father, which is in the spirit…now is that…

B: That’s exactly it…that’s what I’m saying, really. You see we, we transcend our present space and time consciousness and limitation and enter in some measure into the consciousness of Christ which is a non-dual consciousness embracing the whole creation and all the matter. That was a key sentence of Main which I felt…

C: …is that right… It really means putting on the mind of Christ – we become Christ – we become Christ, but we – but there’s also a difference…

B: It’s a difference, yes. We’re “partakers” of the divine nature, you see. I think it’s like the one light is in everyone, you see, but yet all the different colours are there at the same time, you see. There are various images one can use – notes of a symphony. We’re all notes…each is … the individual remains, you see, and yet it’s one with the whole. You know the illustration of the net of Shiva and his pearl necklace. Every pearl reflects the other…and reflects the whole… I think the ultimate state, each one of us, our consciousness is a pure consciousness and it participates in the divine consciousness and yet it participates in its own way. We do retain… the experience we’ve had from the beginning we take with us. We don’t simply discard it.

C: Yes. We take that to the monastery with us too, dont’ we? Our past. All of our experience, and it’s transformed.

B: That’s right.

C: You know, I told you about the three books on Monchanin, the one by Webber, and the one.. Swami Param…

B: …Parama Arubi Anandan…

C: …is that how you pronounce it… and then the book, I don’t remember the exact title, but its forerunner and I guess its almost identical with Ermites du Saccidananda…its something about an ashram…

B: “Benedictine Ashram”

C: “Benedictine Ashram”…did that… later became the..

B: It’s the English version of the much deeper French one, Eremites du Saccidananda.

C: I see, ah… it’s interesting in the one book… the Swami Parama Arubi Anandan…I think that’s your copy…

B: Excuse me one minute. Yes…

C: OK.

B: Nobody there. What’s the time?

C: 4:35

B: We’d better… somebody should be coming at 4:30, but they’re not there… Carry on.

C: So then the…ah…in the one book they don’t even mention Abhishiktananda. He’s not mentioned throughout the book. I thought that was a bit curious…that’s the book you have a little appraisal of Shantivanam in. But throughout the book…there’s a picture of him with a bishop, I thin, but his name is never mentioned in the whole book.

B: Abhishiktananda…He edited it, you know.

C: Oh did he?

B: He edited it, yes.

C: I see. Well that might….that’d be the reason.

B: Yes, yeah.

C: Is there anybody. I don’t see somebody there, so maybe we’d better conclude this. The archetypes. I wanted to ask you about that. Now you seem to say that every person – individual person – has in God a personal eternal archetype, so we’ve always been in God’s consciousness – every single human being.

B: It’s so, yes.

C: Now is that a bit Platonic, would you say?

B: Yes, it’s Platonic surely, but it’s more, you see. It’s Eckhart and the Christian mystics and Ruysbroeck whom I quote, you know.

C: Yes, that’s right.

B: It’s the real mystical tradition and you get it in the other… even the Ibn Al Arabi – Islamic…

C: OK, now it seems like in Plato we would be just sort of a shadow…

B: …yeah…

C: …but you’re not meaning to say that…

B: No. No. Plato is a very limited form of it. The mystics have developed it much more…

C: Right.

B: …and, ah…there’s a fullness, I think, in the archetype, but we’re…we have our reality at the same time.

C: A final question just on yoga…

B: Ah…

C: Now, do you practice any kind of yoga other than sitting…

B: At the moment I don’t. I did for years, you know.

C: Did you…

B: Twenty, thirty years, I should think, yes.

C: How essential or necessary do you think yoga is?

B: I think for many people, you see, the body is the problem, for most Westerners. They don’t develop their body or their breathing, you see, and you’ve got to balance your mind -the mind is dominating and therefore most need some technique or method to become aware of the body and the breath and to bring the body and the breathing into harmony with the mind, you see.

C: So in a way, Christian Meditation might be a way to do that… and sitting perhaps, properly…

B: Sitting and breathing is quite enough normally, but the hatha yoga helps the sitting and so on – quite secondary.

C: I see. I think that John Main said that breathing is …the only thing is don’t stop breathing.

B: (laughing) Yeah, a little negative…

C: Thank you Father, very much. I appreciate it.